The President of Russia, Vladimir Putin, and his allies are responsible for the devastating invasion of Ukraine, which has already led to more than 3.5 million people fleeing the country. In response, forces from across the globe have imposed sanctions on Russia, which are ostensibly targeting Putin and his friends. In reality, though, average Russians are the ones bearing the brunt of these punishments.

The Russian financial system is now quarantined from the rest of the world. The ruble crashed. The Russian economy is on the verge of tanking. Multinational corporations — such as Coca Cola, McDonald’s, IKEA and Apple — under pressure from the public and Western governments, are withdrawing from Russia. Canada, the United States and the European Union have also closed air space to Russian-registered aircrafts, leading to indefinite cancellations of almost all flights in and out of the country. Spotify, Netflix and an array of apps, websites, and services have suspended services in Russia. Meta decided to allow anti-Russian death threats on its platforms, leading Russia to ban Instagram and Facebook in the country.

Ordinary Russian people, in spite of threats of arrests and prison sentences, are protesting the war. And yet, Western governments and corporations are punishing them, doubling down on sanctions and measures that could lead them back to the misery they faced 30 years ago, when the Russian Federation was suffering as a new-born country. Years of hard work, investment and savings have evaporated for working-class families, interest rates have more than doubled, and prices for goods have skyrocketed.

Putin is the source of many great injustices. You can say the same — but much worse — of former president of the United States George W. Bush. And yet, no states and major corporations banded together to demand ordinary Americans lose everything they have as payback for the government’s awful actions abroad. Why should ordinary Russians suffer due to the actions of people they have no control over, who they often don’t even like?

Some pundits are going even further, and explicitly stating that making the average Russian suffer is the point, in order to try to get them to rebel against Putin. As two writers at CNN put it, “The cost of the war in Russian lives and the severe economic downturn Russia will suffer could combine to spur Russian protests and threaten Putin’s hold on power.” Russians aren’t being regarded as humans, but rather mere political pawns, or laboratory subjects, for Western pundits and politicians — in the comfort of their homes — to play with, speculating about just how much pressure will finally push them off the edge to initiate regime change.

But these actions against Russian people aren’t just limited to those within Russia. Instead, we’re witnessing a resurgence of Russophobia throughout the West, including in Canada, which, according to the 2016 StatCan Census Profile, has more than 620,000 people who identify as Russian living in its borders.

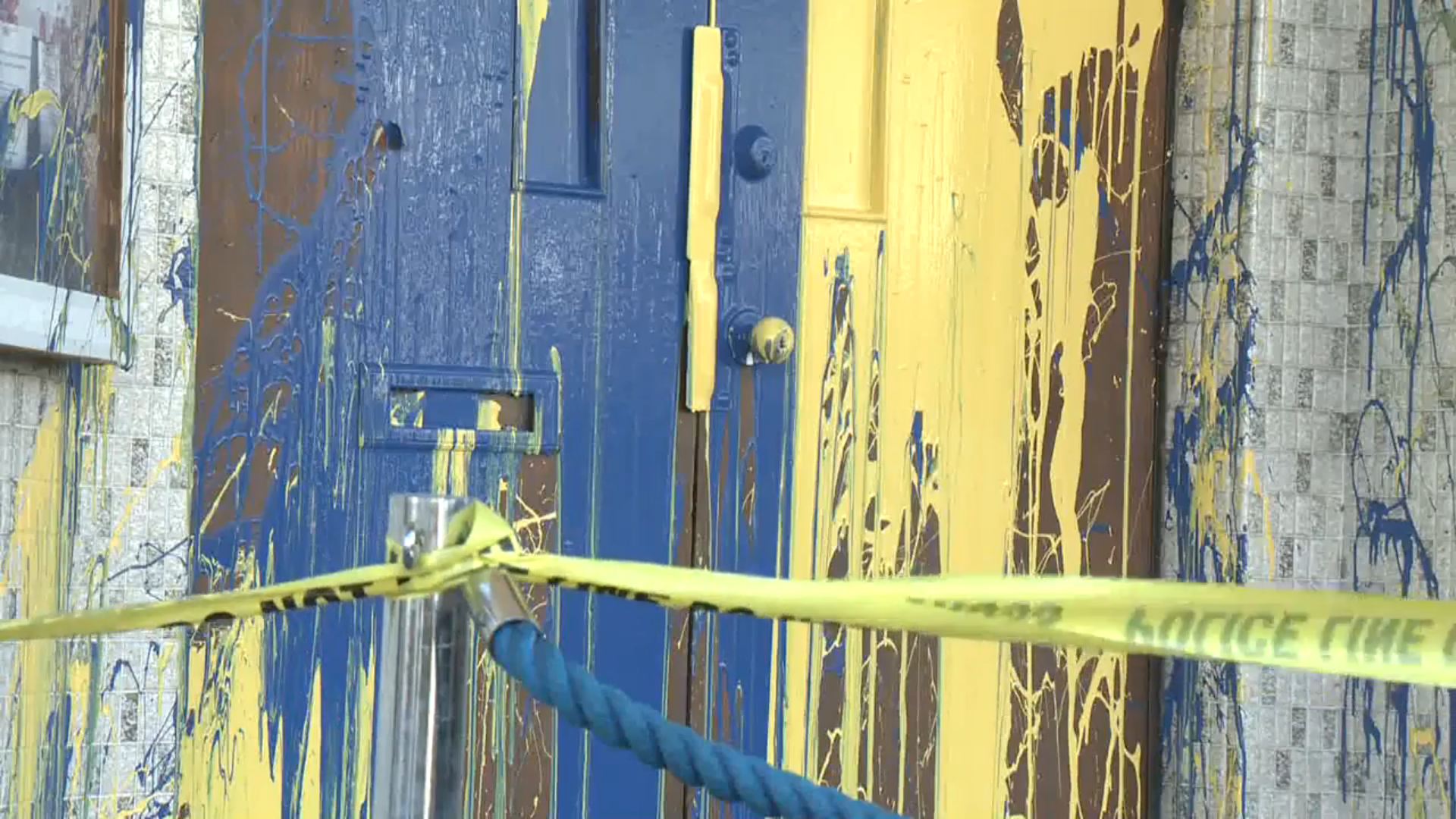

The Montreal Symphony Orchestra and the Vancouver Recital Society both cancelled a pianist’s concert, solely because he was born in Russia. Across Canada, Russian restaurants, churches, community centres and even individuals have been the target of death threats, harassment, or vandalism, leading some to close or try to remove any association with the country from their establishment. In many cases, the victims have expressed solidarity with Ukrainians, or even have relatives in Ukraine, but they are attacked anyways. Some politicians in North America have even encouraged this sort of behaviour. U.S. Democratic Rep. Eric Swalwell, for example, called for the expulsion of all Russian students from the country.

Of course, this sort of behaviour isn’t new. Throughout the pandemic, anti-Asian hate crimes spiked in the west, including by 300 per cent in Canada in 2020. In the days and years after 9/11, we witnessed a deadly rise of Islamophobia. Going further back, Canada forcefully interned or exiled about 21,000 Japanese people throughout the Second World War. And during the First World War, the Canadian government interned more than 8,500 Ukrainians as “enemy aliens,” even though many of them were born in Canada or became naturalized citizens. While things likely won’t go that far, Canadians are repeating the sort of mistakes they’ve made for more than a century.

But these activities and beliefs aren’t just the result of a few isolated individuals that happen to harbour xenophobic views. Instead, our entire media landscape, and opportunistic politicians, are pushing this sort of xenophobia and otherization. And they have a specific goal in mind when they weaponize anti-Russian sentiment: furthering the geopolitical interest of the U.S. and its NATO allies, including Canada, which includes maintaining global hegemony. To justify a hegemony, there must be an enemy, and Russia serves this purpose well.

This is also evident in the sort of tactics that have been wielded against Russia since the invasion, and the double standard in the reaction to them. For example, Poland and Sweden were applauded for announcing that they’d refuse to play in any upcoming World Cup qualifiers against Russia. FIFA would go on to ban the country from the tournament. Meanwhile, in April 2021, Iran was suspended from participating in International Judo Federation events for four years for unilaterally boycotting matches against Israel. The difference in treatment here is because Israel is a NATO ally, while Russia is a geopolitical adversary. Allowing boycotts of Israel would not further U.S. global hegemony, and so the country receives special protection.

But portraying Russia as the enemy isn’t enough. Russian people must also be depicted as dangerous and deserving of punishment, or else the public might not buy the official narrative.

These efforts have been very successful at garnering widespread public support for further conflict with Russia. For example, a poll released earlier this month by Abacus Data found that 65 per cent of Canadians support a NATO no-fly zone over Ukraine, even with the question explicitly stating that it could cause a deadlier war. In fact, 60 per cent of those who support the no-fly zone agree nuclear war is a risk, but call for the tactic regardless.

This is an unfortunate sign the media hasn’t been doing its job, as it’s supposed to report critically instead of amplifying soundbites that fit the government’s agenda.

We can’t afford a third world war, and the likely nuclear catastrophe it would bring. So, we must hold media outlets, pundits and politicians that peddle xenophobia and warmongering to account. They are unjustly harming Russian civilians, Russians abroad and, ultimately, all of us. This includes Ukrainians, who won’t benefit from more war.

Member discussion