On February 11, the 1,765th day after the overdose crisis was declared a public health emergency, the British Columbia Coroner’s Office released its report on the last decade of illicit drug poisoning deaths. It found that from Jan. 1, 2010 to Dec. 31, 2020, 8,741 people in B.C. died due to poisoned drugs. Nearly 20 per cent of these deaths occurred in 2020. Almost half of them happened in the past three years.

After nearly five years of government promises to end the drug death crisis, the situation is worse than ever. The ruling NDP government responded earlier this month by asking the federal government for a provincial exemption to decriminalize drug possession for personal use.

Politicians have been seriously discussing drug decriminalization for at least three years: there was a City of Vancouver report officially recommending it in 2018; B.C. Provincial Health Officer Bonnie Henry advocated for it in 2019; the Vancouver council unanimously voted in favour of decriminalization in 2020.

But decriminalization isn’t a solution by itself. While it’s a step in the right direction, it can’t be the last one.

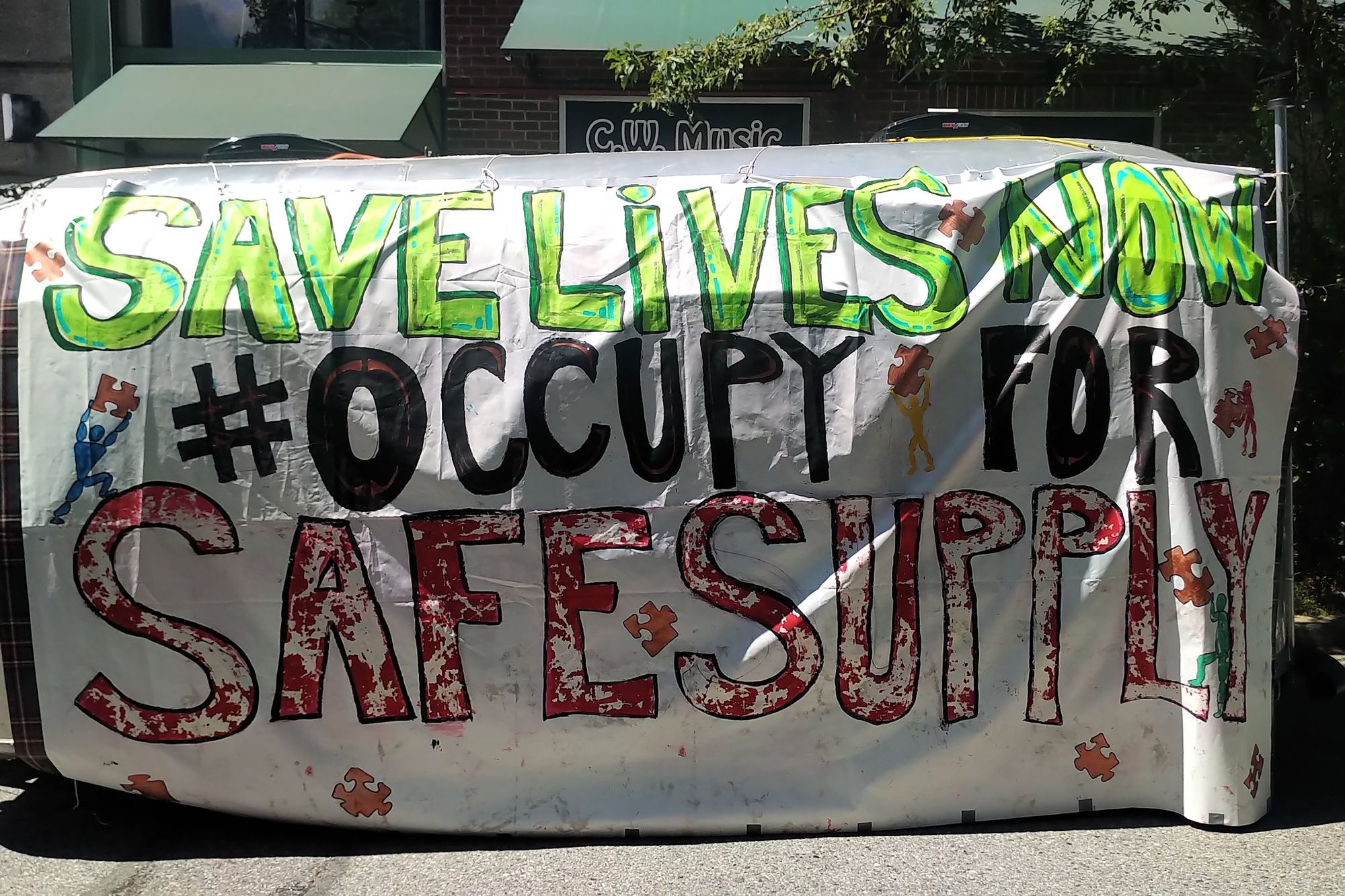

To save lives, B.C. needs to expand its safe supply of pure pharmaceuticals and alternatives so that nobody has to rely on illicit street substances. The province needs to act swiftly, as the pandemic makes the health crisis even more urgent. And it needs to act equitably, to ensure everyone across the province has access to life-saving medicine.

COVID-19 Has Exacerbated The Drug Poisoning Crisis

In some ways, 2019 was a hopeful year in B.C.: drug toxicity deaths dipped to 981, their lowest level since 2015 (but still five times more than the 2000 to 2010 yearly average). Some took this as a sign the province’s drug policy was saving lives. But the pandemic undid those marginal successes.

COVID-19 has been most harmful to already vulnerable people, with marginalized groups both more likely to contract the virus and see negative effects in general.

For one, it’s affecting the supply chain. Closing the United States-Canada border has meant fewer illicit drugs are entering the country, making it more difficult for people who use them to access their normal supply. Substances within Canada are also getting cut with more chemicals, as dealers hope to make their supply last longer.

Fentanyl isn’t the only deadly dilutant that users are worried about. In July 2020, 15 per cent of B.C.’s drug fatalities involved benzodiazepines — depressants that knock users out for longer, can cause respiratory arrest and make users less responsive to overdose-reversing Naloxone. By December, benzos were detected in 50 per cent of drug fatalities in the province.

Another issue is that policies aimed at limiting the spread of COVID-19 led to more people using drugs alone.

People living in single room occupancy hotels and supportive housing in Vancouver were no longer allowed guests, despite the regional health authority’s advice to allow visitors. Safe consumption sites had to close. Houseless residents in Vancouver and Victoria’s tent encampments were moved temporarily to hotels, where they were also required to be alone. More generally, people lost routines, social connections and stability that might have been helping them stay sober or use more safely. Social restrictions instituted in November that ban mixing households currently have no end date.

The B.C. Centre on Substance Use’s advice to “buddy up safely” is much harder to implement in the middle of the pandemic, and this has had a deadly impact.

Safe Supply Needs To Happen Everywhere

Street drugs becoming increasingly toxic wouldn’t be such a major problem if people had access to a government-run system that provided untainted prescription drugs or alternatives.

As of September 2020, around 1,600 people in B.C. who use drugs had received safe supply prescriptions. Up until that point, rules stated that prescriptions could only be given by doctors or specific pharmacists, and only to those at risk of both overdose and COVID-19.

That month, the B.C. government issued a public health order to expand safe supply: allowing registered nurses, and registered psychiatric nurses, to prescribe controlled substances; reducing eligibility requirements to cover more casual drug users; allowing safe supply substances to be dispensed in community and health authority pharmacies.

A month before that, a provincial press release promised more safe injection and inhalation sites, more full-time health workers, and expanded “access to safe prescription alternatives.” Yet besides a couple of new safe injection sites, none of these initiatives have materialized.

“This is an emergency now,” drug policy advocate Karen Ward told Global News in January. “But it doesn’t feel like an emergency. When Dr. Bonnie Henry gives an order, a provincial health order [for] COVID, it’s the next day. Because it matters.”

While limited safe supply continues in the Lower Mainland and Victoria, other communities — including rural or remote areas where residents have less access to doctors and pharmacists — are left in limbo.

News of four more safe supply pilots in Vancouver and Victoria does little to aid drug users outside those urban centres. Smoking accounted for 40 per cent of toxic drug fatalities in 2019, but the only three safe inhalation sites are currently in Vancouver and Victoria.

And although Northern B.C. saw the highest drug toxicity death rate in the province (46 deaths per 100,000 people), there’s been hardly any statements on how the provincial government will help this rural health region. (Liberal MLA Mike Morris, who represents Northern B.C.’s largest city of Prince George, opposes safe supply. There were 58 drug toxicity fatalities in the city last year.)

From B.C.’s first COVID-19 fatality in March 2020 to the end of the year, 901 people died from novel coronavirus. We heard about them in near-daily press briefings. In that same time frame, 1,562 people died from drug toxicity. We heard about them in monthly reports.

How many hundreds more people will die before B.C. rolls out the safe supply they have promised?

Member discussion