After the brazen military aggression against Iran by the United States in Iraqi territory, Iraq’s government demanded U.S. troops leave the country. Canadian Defence Minister Harjit Sajjan has stated Canada will withdraw its military forces in Iraq if formally asked to leave. This is because it’s understood that respect for sovereignty is a basic principle of international relations. Despite this, Canada is enforcing sanctions on North Korea at the same time as the South Korean government is pushing for sanctions relief.

In 2019, Canada committed military vehicles to enforce United Nations Security Council (UNSC) sanctions against North Korea, which were written in response to the state’s missile tests and nuclear weapons program. These vehicles include Halifax-class frigates, which can target submarines, other ships and airplanes, as well as large Aurora airplanes used to support the destruction of Libya in 2011. They will remain near North Korea’s borders until at least 2021.

Canada also imposed its own sanctions on North Korea in 2006 and 2011, under the “Special Economic Measures Act.” The sanctions from 2006 to 2010 targeted individuals and exports, and began in response to nuclear tests by North Korea. In 2011, John Baird, then foreign affairs minister, used the “Special Economic Measures Act” to ban Canadians trading goods with, or investing in, North Korea, citing as a justification the contested sinking of the South Korean ship “The Cheonan.”

Sanctions are often presented as an alternative to war, and a way to target elites instead of the general population. In reality, sanctions have a major impact on the lives of all North Koreans.

A 2019 report from anti-war group KoreaPeaceNow found that medical supplies and equipment, including ultrasound machines and orthopedic appliances for people with disabilities, aren’t allowed under UNSC sanctions that have been passed since 2016. Although exemptions are sometimes granted, the significant delays they end up producing often prevent North Koreans from getting aid when needed. The delays are estimated to have caused the deaths of more than 3,000 Korean children in 2018 alone due to malnutrition and lack of medicine.

Both Canadian and UNSC sanctions currently in place on fuel and machinery are ostensibly for targeting the military, but they also make farming in North Korea more difficult, which is especially dangerous considering the lack of arable land.

Additionally, the UNSC sanctions on foreign currency, supposedly for targeting leadership, actually make it difficult to impossible for humanitarian organizations to operate in the country, as most banks refuse to work with any organization associated with North Korea due to the risk of being sanctioned.

In 2019, the Finnish NGO Fida announced that it ended its humanitarian program in North Korea, which had existed since 2001, due to the UNSC financial sanctions. As a result, North Koreans lost out on €300,000 in planned funding for Fida in 2019.

South Korea’s current president, Moon Jae-in, was elected in May 2017 on a mandate of economic justice and peace with North Korea. His proposed policies fit into the tradition of the “Sunshine Policy,” which believes the best way to open up North Korea and improve conditions is through economic and cultural engagement. Kim Dae-jung, South Korea’s first president not from the ruling regime, implemented the policy and won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2000 for his efforts.

There was a major breakthrough in relations between the two countries during the 2018 Olympics, when North and South Korea marched under one flag. However, since then, Moon and his administration have found themselves sidelined in negotiations by Western states insisting upon sanctions.

In 2018, South Korea’s Foreign Minister, Kang Kyung-wha, suggested sanctions could be reduced in order to allow tourism into North Korea. Cooperation between North and South Korea on projects such as tourism is important to lay the groundwork for Moon’s campaign pledges to build a rail network between Russia, China, and South and North Korea. In response to Kang, U.S. President Donald Trump bluntly stated that South Korea, “Won’t do that without our approval.”

This year, meanwhile, Moon’s statements that he would seek exemptions to UN sanctions in order to restart negotiations was met by a stern remark from U.S. Ambassador Harry Harris, who stated such moves first need to go through America and its joint working group.

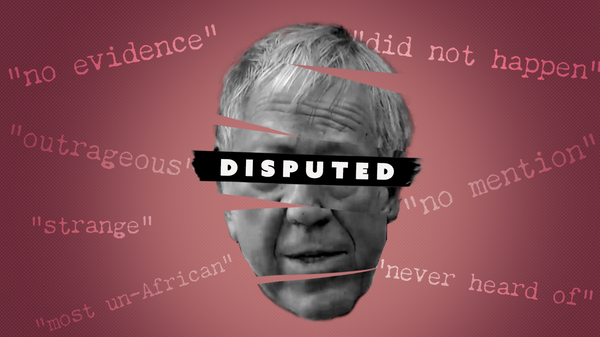

Foreign interference in inter-Korean relations has resulted in a backlash from South Koreans against Harris. His blunt manner and facial hair resemble a Japanese colonialist ruler as portrayed in Korean television dramas, but criticism of his policies is anything but superficial, reflecting frustration with the U.S. and other countries for impeding moves toward peace by both North and South Korea.

In October 2019, Harris’ residence was occupied by Korean university students who protested the U.S. government’s demand that South Korea increase its payment for their military bases by 400 per cent. The protesters unfurled a banner that stated, “Get out of the country.” Harris responded to a South Korean official’s apology for the occupation by saying, “You should be sorry. It is your responsibility.”

The backlash toward the U.S. and other Western countries from Koreans is justifiable, especially when considering the role they played in bringing the two countries where they are now.

The border between North and South Korea was drawn by the U.S. military in 1945 without any consultation from Koreans. In 1948, the UN held separate elections for North and South Korea, which were boycotted in the North as they legitimized the division of Korea.

The elections in Jeju, a small island to the south of the Korean peninsula, resulted in mass protests and eventually armed struggle against the South Korean government. The government responded with a scorched earth policy that killed 30,000 Koreans, 10 per cent of the island’s population. Government police forces and anti-communist militias also engaged in torture and mass executions. This was done with the knowledge of the U.S. military.

North Korean leadership was made up of independence fighters who fought the Japanese, while South Korea was run by Japanese collaborators without popular support. The U.S. backed South Korea, seeing it as a chance to contain the spread of communism in Asia. The division interrupted a historical process of righting the wrongs of Japanese colonialism, and ultimately made the Korean War inevitable.

The war, which began in 1950, was marked by a massive aerial campaign against North Korea, where the U.S. alone dropped 635,000 tons of bombs, more than during the Second World War in the Pacific. An estimated 10 per cent of Korea’s population, approximately three million people, was killed, with the majority of deaths in North Korea. The conflict resolved nothing and left the peninsula divided and still technically at war.

Canada contributed more than 26,000 soldiers and eight destroyers to the UN force, and took part in heavy combat. In 1951, future-Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson described Korea as similar to colonial wars against Indigenous people, stating, “If [Canadians] stuck to the plow and left the rifle at home, they would have been easy victims for any savages lurking in the woods.”

Troubling reports of war crimes by UN forces persist to this day. Official documents reveal that the U.S. Air Force was permitted to shoot civilians approaching UN military lines, with the excuse that North Korean soldiers could be hiding among civilians.

Canada has also been accused of committing war crimes going back to 1951, when a Korean man named Shin Hyun-Chan stated that a Canadian soldier shot members of his family, killing his father and wounding his mother and sister. That year, a Canadian was tried and found guilty, but was exonerated after returning to Canada. Shin decided to go public with his story after reporting in 1998 about the massacre of Korean civilians by American soldiers. His story is one of many during the Korean War of Canadians being tried for war crimes in Korea and being exonerated back home.

Sanctions punish all Koreans, are ultimately unwanted by both the North and South Korean governments, and stand in the way of peace. As such, and with Canada’s historical wrongs in mind, the Canadian government should end the military deployment in Korea and lift its own sanctions.

All Koreans will be better off as a result.

Member discussion