If you believe exit polls from Tuesday’s Democratic primaries, socialism is in. Voters in California, North Carolina and Tennessee all told pollsters they viewed socialism more favourably than unfavourably. In Texas, of all places, it wasn’t even a close contest: 57 per cent viewed socialism favourably compared to only 37 per cent who saw it unfavourably.

Socialism’s renaissance is not limited to the United States. Here in Canada, a poll from last summer found that 58 per cent of people have a favourable view of socialism.

These sorts of numbers must be astonishing to those firmly ensconced in the political class, where socialism has been viewed for generations as a joke at best and, at worst, a step down the road to gulags and struggle sessions.

But voters are on to something that political elites are missing. Far from being a radical idea that has (as they are fond of saying) never worked anywhere, evidence of socialism’s value are all around us today. In fact, one of the best proof-of-concepts for a modern democratic form of socialism can be found in an unexpected place: the Canada Pension Plan Fund.

Every Canadian at some point in their lifetime will receive payments from the Canada Pension Plan (CPP), and they have the Canada Pension Plan Fund at least in part to thank for that. CPP payments are funded by contributions made by employees and their employers over the course of their working life. But left to stagnate in a savings account, these contributions would not cover the cost of paying out benefits during our retirements. This is where the Fund — and the Canadian Pension Plan Investment Board (CPPIB), which oversees the Fund — comes in. Their job is to pool those contributions and invest in assets around the world which then grow in value and generate returns, some of which are reinvested and some of which are paid out to CPP recipients. The CPPIB is, essentially, a big private equity investor (one of the world’s largest, in fact).

None of this may sound very socialist to you. But consider: an important aspect of socialism is an economic arrangement in which the means of production are commonly owned by the public rather than by private capitalists.

The basic function of the CPPIB is to extend public ownership over the means of production through the CPP Fund. Of course, this is not made explicit. The stated mandate of the Board is to “maximize long-term investment returns without undue risk.” But because it’s a Crown corporation ultimately owned by and accountable to the Canadian people, what this means in practice is that the CPPIB seeks to bring more and more assets under public ownership.

Because of the Fund’s investments, every Canadian is now an indirect shareholder in some of the world’s largest companies. CPPIB invested $786 million in the Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba in 2011. They co-own a 17 per cent stake in Viking Cruises. And last year, they bought a $200 million share in a Canadian company, Premium Brands, which makes about half of the pre-packaged sandwiches in the country, including those sold at Starbucks. In total, the Fund owns over $420 billion in assets, and has returned $251 billion in returns over the past 10 years.

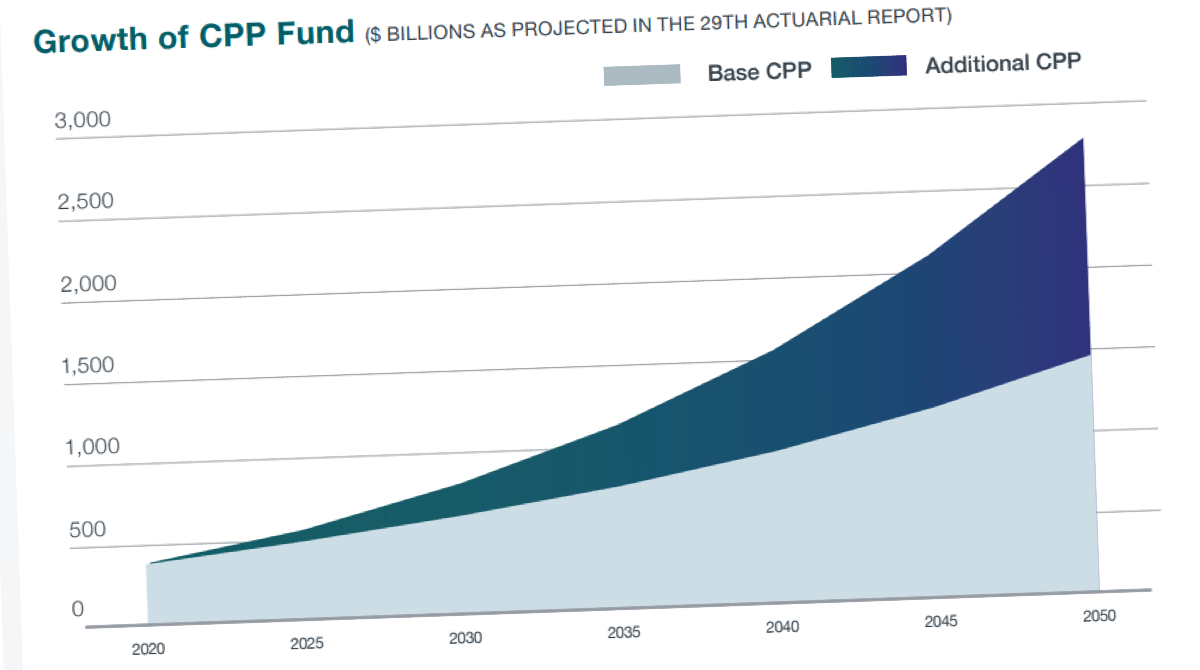

Canadians get real benefits from these ownership stakes. Thanks in part to returns generated by the Fund, workers retiring in 2050 with 40 years of CPP contributions will enjoy an extra $2,500 each year in retirement benefits. That will jump to an extra $4,000 per year for workers retiring in 2065. These are the fruits of public ownership, and a real example of a socialist institution delivering the goods.

Public pension funds are such a familiar part of our capitalist landscape that it seems bizarre to regard them as examples of actually existing socialism. But in fact, there is a long and rich strain of democratic socialists who have argued that large funds such as these could provide the infrastructure for a fully socialized economy. The Social Democratic government of Sweden even began implementing a version of funds socialism with the Meidner Plan in the early 1970s, a project which was ultimately abandoned by a right-wing coalition that came to power in 1976.

The godfather of this “funds socialism” is Rudolf Hilferding, an Austrian economist who was a top thinker in Germany’s Social Democratic Party during the Weimar years before he was tortured and murdered by the Gestapo in 1941. In his seminal 1910 work, Finance Capital, Hilferding noticed that financial institutions were driving the centralization of capital ownership in the economy, and pointed out that rather than a setback this should be regarded as a boon for the socialist project he wanted to bring about:

“The socializing function of finance capital facilitates enormously the task of overcoming capitalism. Once finance capital has brought the most important branches of production under its control, it is enough for society, through its conscious executive organ – the state conquered by the working class – to seize finance capital in order to gain immediate control of these branches of production.”

Hilferding thought capitalism’s financiers were unwittingly doing the socialist’s job for them, centralizing control of the economy within a few firms which could then be seized by the public in one fell swoop. Precisently, he realized this would not only be an effective way of bringing the economy into public ownership, but would also avoid the messiness that often accompanies state expropriation:

“There is no need at all to extend the process of expropriation to the great bulk of peasant farms and small businesses, because as a result of the seizure of large-scale industry, upon which they have long been dependent, they would be indirectly socialized just as industry is directly socialized. It is therefore possible to allow the process of expropriation to mature slowly, precisely in those spheres of decentralized production where it would be a long drawn out and politically dangerous process. In other words, since finance capital has already achieved expropriation to the extent required by socialism, it is possible to dispense with a sudden act of expropriation by the state, and to substitute a gradual process of socialization through the economic benefits which society will confer.”

The managers and analysts at the CPPIB have likely never heard of Hilferding, and almost certainly do not regard themselves as his acolytes. In effect, however, their work is doing exactly what he recommended: indirectly socializing large swathes of the economy through a publicly-owned investment fund.

The obvious critique of the CPP Fund from a democratic socialist perspective is that it’s undemocratic. Canadians may reap the rewards of its growth, but have no actual control over its function. Decisions are made by hired guns — fund managers instructed to maximize returns without regard to other concerns. Citizens do not have a say in how the Fund’s resources are allocated, or how the companies owned by the Fund operate.

This is true, but does not necessarily need to be the case. The CPPIB is a creature of Parliamentary legislation, and its mandate can be adjusted by Parliament. If voters wanted to, they could elect a government that would, for example, modify the CPPIB’s mandate to force divestment from fossil fuels. Norway’s social wealth fund — the largest in the world — has done just this.

Matt Bruenig, the founder of the People’s Policy Project think tank, has sketched a proposal for a social wealth fund that would be democratic by design. Under his scheme, the fund exercises its right to vote on shareholder matters of the companies it owns a stake in. The elected government would instruct the fund on how to cast its vote, in effect allowing elected representatives to influence corporate direction. For example, a government so inclined could use the fund to vote down lavish CEO pay packages, or oust executives who threaten worker pensions. There is nothing inherently undemocratic about funds socialism, though most publicly-owned funds today are admittedly not run democratically.

The CPP Fund is not a perfect model for how the economy could be socialized through publicly-owned funds. Aside from its undemocratic structure, it’s also small relative to the size of the economy, a publicly-owned buoy floating in a sea of private ownership. But it’s still an effective proof of concept for socialism. We can imagine a scaled-up version of the CPP Fund, its capital reserves boosted through wealth taxes or leveraged asset purchases, buying an ever greater portion of Canada’s assets and distributing the returns on those assets to all of us equally in the form of dividends.

Using institutions like investment funds traditionally associated with capitalist economies will be off-putting to many socialists. Some will think it assigns too much power to the state. Others will object that its reformist, and what’s needed is revolution. Disagreements like this are nothing new to the socialist community, but the variety of funds socialism I have argued for can sit comfortably within a democratic socialist framework.

All of us sharing equally in the fruits of growth and citizens empowered to democratically determine questions about how to run and manage the economy: that’s the democratic socialist vision, and it’s achievable through institutions that look a lot like ones that are already working today. The CPP Fund is not some radical pie-in-the-sky idea — it’s a trusted institution that secures retirement and real material benefits for millions of Canadians. It’s also a proof-of-concept for democratic socialism.

Member discussion