Over the course of 11 days in May, Israeli bombardment of Gaza killed more than 230 Palestinians, at least 65 of them children.

While this was ongoing, hundreds of journalists signed an open letter decrying the “lack of nuanced Canadian media coverage” of Israel’s oppression of Palestinians. One of the issues they brought up was “Canadian style guides still ban[ning] the use of the word ‘Palestine’ in coverage.”

In many, if not most, mainstream Canadian newsrooms, journalists are forbidden from using the word “Palestine” in writing and broadcasts except under limited circumstances — like referring to the name of an organization, such as the Palestine Liberation Organization.

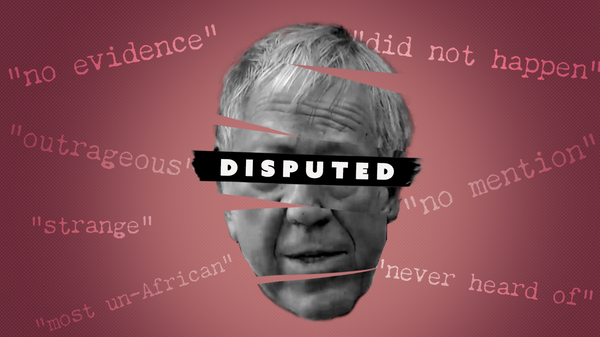

Many journalists have been admonished for doing so, with the most galling public case of this being CBC forcing radio host Duncan McCue to apologize on-air for using the word a day earlier, as well as removing references to the word from subsequent broadcasts of the interview.

If newsrooms are ever going to improve their coverage of Israel and Palestine, they’ll need to first allow employees to note that the latter is a real place. Here is a breakdown of the reasons newsrooms bar the use of the word Palestine, why they don’t hold up, and who this practice serves.

The Canadian Press Style Guide, which is the industry standard for copy issues, contains no guidance on proper terminology regarding Palestine. As such, newsrooms have come up with their own internal guidelines on the matter, as they do with many issues.

While the specifics of each guideline likely vary, the CBC’s stance on the matter is a good stand-in for the industry at large. Here it is, at its full length:

Palestine vs. Palestinian territories — There is no modern country of Palestine, although there’s a movement to establish one as part of a two-state peace agreement with Israel. So do not refer to Palestine or show a map with Palestine as a country. Use the term “pro-Palestinian” instead of “pro-Palestine” when referring in generic ways to Palestinian supporters. Areas under the control of the Palestinian Authority are considered Palestinian territories: Fatah-run West Bank and Hamas-run Gaza Strip. The terms Palestinian territories and occupied territories are not synonymous. The former includes the Gaza Strip, where Israel no longer maintains a permanent military presence. The latter includes the Golan Heights, which Israel and Syria are at odds over. In November 2012, the United Nations voted to grant “non-member observer state” status to Palestine. We can accurately mention this in stories when relevant. But the UN does not grant nationhood, and it remains premature to call Palestinian territories the country of Palestine. When making references to historical Palestine, use clear language (e.g., “British Palestine” is the accepted term for the British Mandate of Palestine, which administered the region between 1920 and the birth of Israel in 1948).

The CBC says it hasn’t used the word Palestine as a proper noun since the early ’70s, with this version of the policy first being released in July 2011 and since updated.

In September 2020, Hanna Kawas, the chair of the Canada Palestine Association, lodged a formal complaint with CBC Ombudsman Jack Nagler about McCue’s apology. He has since publicly critiqued the CBC’s justification for keeping the word Palestine out of the news, on several grounds. One particularly interesting one Kawas points out is the inconsistency with which Palestine is treated compared to other places.

Kawas writes, “It is interesting to compare CBC’s approach to language around Kosovo. Kosovo is not a member of the United Nations in any capacity, it is recognized by fewer countries in the world than the state of Palestine, yet CBC is happy to use the proper term Kosovo in its reporting. The only difference we can see is that the Canadian government has officially recognized Kosovo, but not Palestine.”

Responding to Kawas’ claim, Nagler said he believes the Canadian government played no role in determining CBC’s editorial policies, but admits, “There is no consistent, established set of criteria that CBC uses to decide which politically-disputed areas get ‘recognized’ in its language guide.”

Meanwhile, Paul Hambleton, the CBC director of journalistic standards, has also admitted that the entry is based in part on “foreign affairs positions articulated by Canada and various other western countries.” Hambleton has also attempted to justify the CBC’s position by writing, “Global Affairs Canada does NOT use the proper noun ‘Palestine’ in its overview of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.”

So, even if the Canadian government doesn’t tell the CBC what its policy should be directly, the foreign affairs department’s decisions ultimately determine what words the network and the industry at large will use. It’s the only way you can read Nagler’s rationale for Kosovo to be allowed but Palestine barred.

The CBC’s guidance on the use of the word Palestine does not serve the truth or the public, but rather an Israeli narrative that the Canadian government is happy to support.

Kawas writes, “As CBC seems to fully understand that language is an important component of defining issues, we assume that they also understand that their policy makes them complicit in trying to eradicate Palestine’s national identity. This has long been a pillar of the Zionist project, which goes to great lengths to ensure that the Palestinian struggle is not framed as a national struggle against settler-colonialism.”

Israel has worked against the two-state solution, and the CBC’s Palestine entry aids this by accepting that one is a state, and the other is a series of disputed territories with unsettled borders. But how can borders be determined as Israeli settlers continuously gobble up land in the West Bank, and force Palestinians from their homes in Jerusalem neighbourhoods like Sheikh Jarrah? These are actions supported and encouraged by the Israeli government. The CBC, and other outlets, buy into this project by refusing to let journalists call Palestine by its name, thereby further affirming Israeli domination.

It also does so by attempting to erase the history of Palestine to make it appear as though it never existed. As Kawas writes, “Even if one puts aside CBC’s argument on Palestine not yet being a ‘sovereign country,’ why this obsession with removing any usage of the word Palestine in nearly all other contexts, including generic or historic ones? The ‘British Palestine’ reference seems particularly ridiculous and archaic in post-colonial times.”

Since the release of the open letter, many journalists at the CBC have been pulled off coverage of the issue. Explaining the decision in an email to staff, Brodie Fenlon, editor-in-chief of CBC News, said the letter-signers failed to live up to CBC standards demanding that they “won’t take a public position that ‘affects the perception of impartiality and could affect an open and honest exploration of an issue.’”

And yet, despite their ostensible desperation to appear to not be ‘taking a side,’ CBC and many other newsrooms have rules in place ensuring they do just that. By refusing to call Palestine, Palestine, media organizations have further entrenched their pro-Israel bias.

Member discussion