A cenotaph dedicated to Ukrainian veterans of a Waffen SS division has been removed from a cemetery in Oakville, Ontario, but its ultimate fate has not yet been determined, according to sources.

Speaking on condition of anonymity, a source with knowledge about the cenotaph’s removal told The Maple that the church council came to a unanimous decision to have the cenotaph permanently removed from the cemetery grounds.

The cenotaph honours veterans of the 14th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS, also known as the “Galicia Division,” which was formed primarily of Ukrainian volunteers who fought with the Nazis during the Second World War.

According to the source, the cenotaph is now off the cemetery’s property and in the possession of a contractor for refurbishment. While it isn’t clear where the cenotaph will end up, the source insisted it will not return to the St. Volodymyr cemetery.

The now-removed cenotaph is one of several in Canada that honours fascists and Nazi collaborators. Attention to these monuments was rekindled after members of Parliament rose to honour Yaroslav Hunka — a Galicia Division veteran — as a “Ukrainian and Canadian hero” last September.

The source told The Maple that increased attention since the scandal has resulted in visits from the far-right to the cemetery, including pilgrimages by neo-Nazi groups. The monument was defaced with anti-fascist graffiti in 2020.

The source emphasized that St. Volodymyr’s neither owns the cenotaph nor commissioned its construction, and that the initiative to commemorate veterans of the Galicia Division was the responsibility of the veterans themselves.

After the church decided the cenotaph should be removed, they contacted approximately 30 stakeholders. The majority of these were descendants of the buried Galicia Division veterans, along with a handful of surviving veterans, including Hunka.

The source indicated that the descendants had at one point wanted the cenotaph to be repaired and reinstalled in the same location, something the church refused.

Rabbi Stephen Wise, a leader in Oakville’s Jewish community who was mentioned in several early reports about the cenotaph’s removal, confirmed the information passed on by the anonymous source.

He further commended the Ukrainian community of Oakville for taking the initiative to have the cenotaph removed.

Early Reports Conflicted

Early reports offered conflicting accounts of what was to become of the cenotaph.

A viral video of the cenotaph’s removal circulated in a social media post that falsely suggested the cenotaph had been “demolished.” Subsequent reporting by the National Post suggested that the monument might be returned after being repaired.

According to the anonymous source, other individuals and organizations who were credited in early reports for their alleged involvement in the cenotaph’s removal – including MPP Effie Triantafilopoulos, Oakville Mayor Rob Burton and B’nai Brith Canada – were not in fact involved.

Some confusion may have been caused by misinformed cemetery employees handling media questions, according to the source.

The Friends of Simon Wiesenthal Centre (FSWC) celebrated the cenotaph’s removal, and further called for the removal of another Galicia Division cenotaph and a monument to Roman Shukhevych that is still standing in Edmonton. Shukhevych was the wartime leader of the far-right Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA).

FSWC made no mention of a monument to the UPA that stands in the same Oakville cemetery, however.

“The UPA memorial is, arguably, more problematic,” said Per Anders Rudling, a historian at Lund University and an expert on nationalism and ideological history in the post-Soviet successor states and their overseas diasporas.

“The UPA carried out atrocities on a massive scale — much more so than the Galicia Division.” Rudling said nearly 80 per cent of the UPA’s officers were former collaborators with Nazi Germany.

The UPA was the armed wing of the Stepan Bandera faction of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN-B). Bandera was the far-right wartime leader of the more militant wing of the OUN.

The core of the UPA consisted of former German army auxiliary police, later joined by Waffen-SS volunteers.

“Led by Roman Shukhevych, the UPA killed over 90,000 Poles, and upwards of 10,000 Jews,” said Rudling. “The OUN-B was totalitarian, antisemitic, and engaged in mass ethnic cleansing.”

Despite the UPA’s well-documented involvement in the Holocaust, those taking responsibility for the removal of the Galicia Division cenotaph seem unaware of the monument dedicated to UPA veterans.

The anonymous source indicated they are aware of the monument, but not of the history of the UPA.

Rabbi Wise was unaware of both the history of the UPA as well as the presence of a monument dedicated to it.

“I can’t really comment on it, but if its people were complicit in the Holocaust, then I would be equally in favour of its removal,” said Rabbi Wise.

Entangled Histories

There is considerable confusion between the Galicia Division and the UPA, a problem exacerbated by the presence of monuments to both organizations in close proximity to one another in Oakville and Edmonton.

Rudling provided The Maple with a scanned copy of a program for the unveiling of the Oakville UPA monument in 1988. The cover includes a sketch of the figure that appears on the monument, as well as the OUN slogan “achieve Ukrainian statehood or die in the struggle for it,” as well as “UPA” in Cyrillic.

Rudling believes the construction of the UPA monument was intended to coincide with the “millennium of the Christianization of the Rus,” referring to the thousand-year anniversary of Ukraine first becoming a Christian nation in 988.

“The primordialist nationalist narration insists Ukraine was Christianized in 988, but the term ‘Ukraine’ came much later, and Ukraine as a political project is largely a 19th century project,” said Rudling.

This millennial celebration coincided with resurgent Ukrainian nationalism as the Soviet Union collapsed.

“Most of the Waffen-SS veterans were born in the 1920s, so by the mid-1980s they were starting to die,” Rudling said. “They needed a big necropolis where they could glorify their martyrs.”

In addition, the monuments were built shortly after the conclusion of the Deschênes Commission, an investigation into war criminals alleged to be living in Canada.

Controversially, the Deschênes Commission concluded that Galicia Division veterans should not be held responsible as a group for war crimes, despite the fact that the entire SS was determined to be a criminal organization at the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg in 1946.

The commission further determined that charges of war crimes against the Galicia Division had never been substantiated.

As reported in Esprit de Corps, the commission’s conclusions were criticized at the time as a whitewash.

“The Waffen-SS Galicia Division was a collaborationist unit,” said Rudling. “The SS was the Nazi Party’s army, and its members took personal oaths of allegiance to Hitler. They remained loyal to Germany right until the end of the war.”

While some Galicia Division veterans and their supporters considered the Deschênes Commission’s conclusions to be a vindication of their innocence, care seems to have been taken to avoid mentioning the unit on the Oakville cenotaph directly.

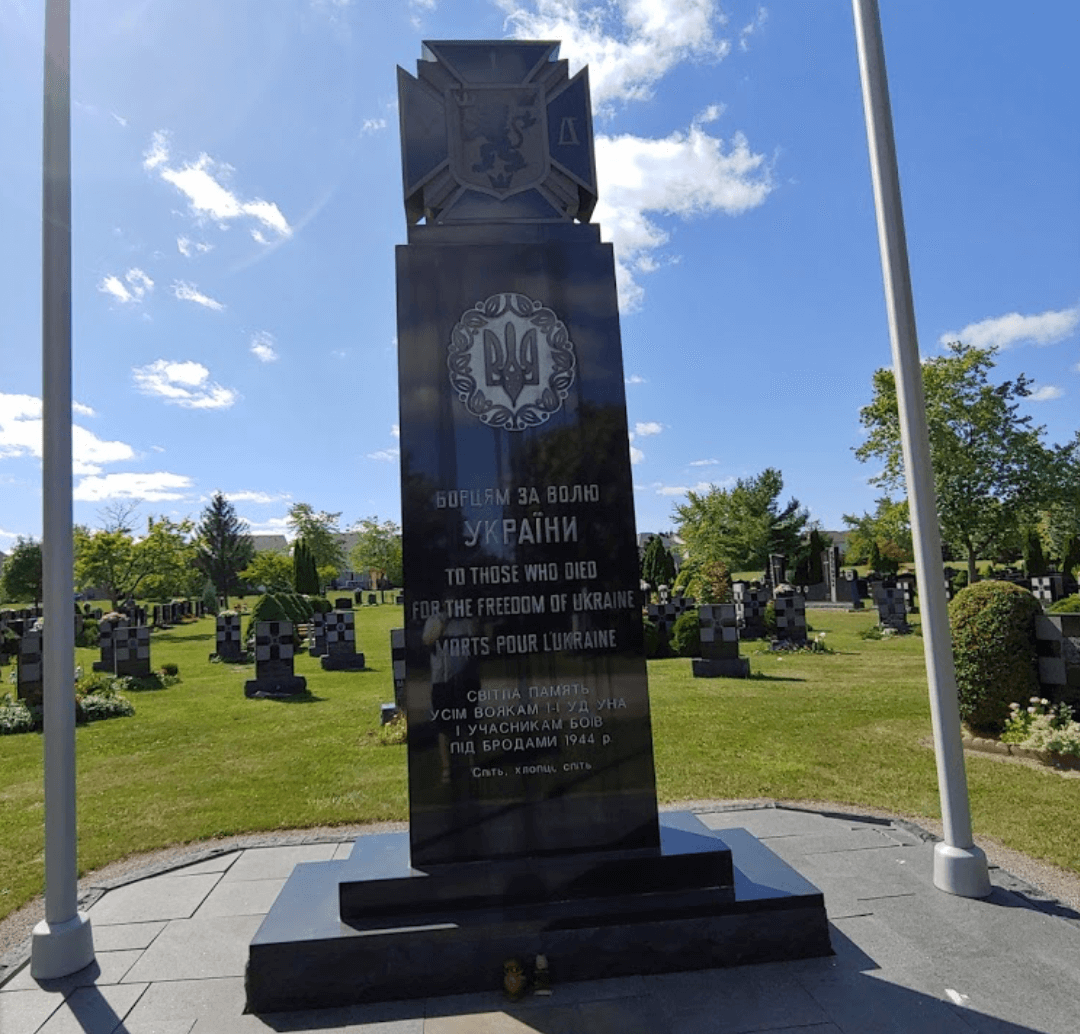

The cenotaph appears to have two inscriptions, distinguished by font and the appearance of age. What appears to be the original inscription reads “To Those Who Died for the Freedom of Ukraine.”

A second inscription, located at the bottom of the cenotaph, reads “In Memory of Combatants From the 1st Division of UD-UNA and Those Who Fought in Defence of Brody in 1944.”

The “Defence of Brody” refers to a battle that took place during the Second World War in 1944. The Galicia Division participated in the battle, and many of the survivors later joined the UPA.

“UD-UNA” refers to the 1st Ukrainian Division of the Ukrainian National Army.

Although neither “Galicia Division” nor the “14th Waffen-SS” appear to have ever been engraved on the cenotaph, the symbol of the UNA sits prominently atop it.

Photos of the monument taken several years ago show the identical headstones of veterans buried near the cenotaph, each adorned with the same symbol.

“The euphemism ‘1 UD UNA’ is a post-war construct,” said Rudling, who added that plans to transfer the Galicia Division to the control of the collaborationist Ukrainian Central Committee were not fully implemented by the time the war ended.

“As a fighting unit the 1 UD UNA did not really exist.”

The ongoing fallout from last fall’s Nazi Parliament scandal has shone a light on an otherwise little known and very dark chapter of world history.

“This episode raises larger questions about whether Canada needs monuments to totalitarian groups with well-documented legacies of mass murder,” said Rudling, who also cautioned against painting all Ukrainians with the same brush.

While there is a politically active community of ultra-nationalists who are supporters of the Bandera faction of the OUN, Rudling noted the vast majority of Ukrainian Canadians have no interest or involvement in Nazism, fascism or the far right, either today or 80 years ago.

“There was a powerful leftist current in the interwar Ukrainian Canadian community. During the Second World War, many Ukrainian Canadians fought Nazi Germany, and millions of Soviet Ukrainians died fighting the Nazis.”

Taylor C. Noakes is an independent journalist and public historian from Montreal.

Member discussion