An upsurge in union organizing in the United States this year has been an inspiration to many there, as well as in Canada and beyond. Now seems like a good time to take stock of the American labour movement.

Last month, the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), the federal agency tasked with overseeing union certification elections and enforcing labour law in the U.S., reported that petitions for union elections have increased by 58 per cent so far in 2022, relative to last year’s figures. In the first three quarters of the current fiscal year, the NLRB has received 1,892 “representation petitions,” i.e. union applications for elections to represent new bargaining units.

This is no doubt positive news. It should, however, be placed in context. From 2012 to 2015, petitions for union elections were growing slightly year over year, going from 1,974 petitions in 2012 to 2,198 in 2015, the last peak year.

Since 2015, U.S. union election petitions have been declining annually, and at a troubling pace, particularly when adjusted for labour force growth. By 2021, petitions were down to only 1,440 for the entire fiscal year. So, 1,892 applications thus far in 2022 is indeed a promising development, but it also indicates that U.S. union elections are simply on track to return to their 2012 to 2015 levels.

As union observers across North America know well, the longer term trends are even more depressing. I recently gathered all of the NLRB’s data on union representation petitions since the agency was founded with the National Labor Relations (Wagner) Act in 1936. As you might have guessed, since the late 1970s the story hasn’t been good, as the following graph shows.

After its founding, the NLRB, with its mandate to promote and protect collective bargaining, aided a growing labour movement and applications for union elections climbed impressively. With the passage of the Labor Management Relations (Taft-Hartley) Act in 1947, unions faced a series of new hurdles and restrictions on their activities, including bans and limitations on various forms of strike activity and a requirement that union leaders swear under oath that they weren’t communists. Despite an initial drop off in applications following Taft-Hartley, from the late-1950s to the mid-1970s, representation petitions grew by leaps and bounds.

In 1976, unions filed more than 15,000 new applications for union elections. Since that year, representation petitions have dramatically fallen off in the face of neoliberal labour market deregulation, corporate globalization and the off-shoring of manufacturing jobs, along with a truly remarkable employer offensive. Despite a few moments of promise — often following commitments from unions to reform their organizing strategies — American labour has been unable to reverse its decline.

It’s also worth bearing in mind that we’re talking about petitions to hold a union election, not the election itself. In many cases, an election is never held, either because the union withdraws the application or the Board dismisses it for some reason (for example, because the union hasn’t demonstrated that the required proportion of workers in the potential bargaining unit — 30 per cent — are behind the union). Over the past decade, the number of petitions that proceed to an election has fluctuated between roughly 60 and 72 per cent. In the vast majority of instances where an election isn’t held, it’s because the union withdrew its application, often due to intense employer opposition.

There’s then the question of how often unions actually win NLRB elections and certify new bargaining units. On this front, there’s some good news. The union win rate in the U.S. has improved quite a bit between 2012 and 2021, rising from just under 65 per cent to nearly 77 per cent. Yet this higher win rate hasn’t been enough to offset the decline in representation applications: 1,120 bargaining units were certified in 2015, while unions secured only 663 in 2021. You can’t win if you’re not in the game.

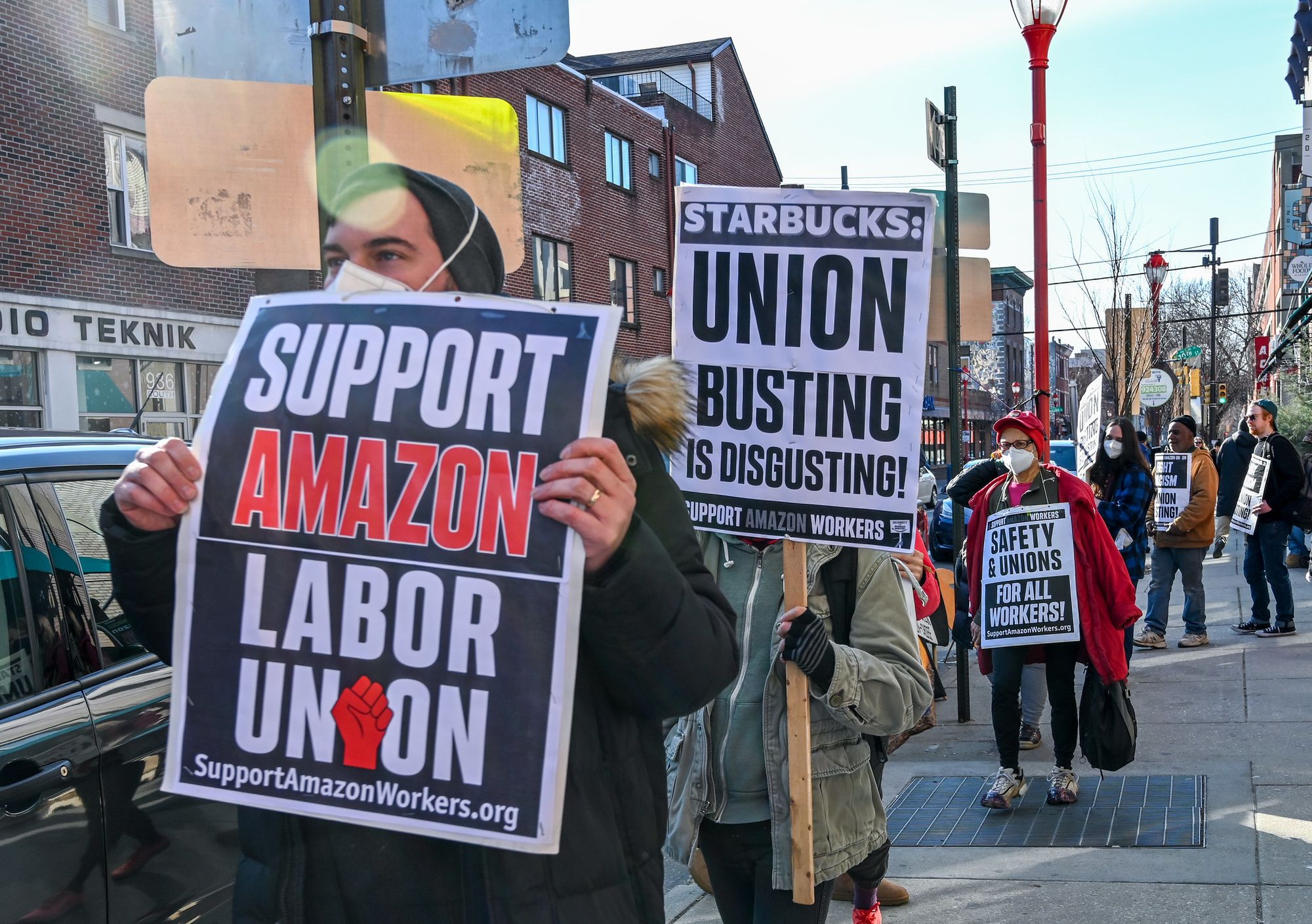

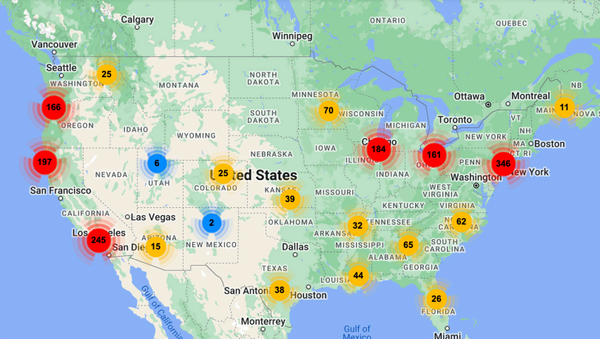

In 2022, with more union elections before the NLRB, the higher union win rate is making some difference. As Robert Combs at Bloomberg Law reports, unions’ total wins so far this year are at a 20-year high. A good deal of this new labour momentum is coming from high-profile organizing drives, such as those at Amazon and Starbucks. Although Combs argues that Starbucks Workers United’s small bargaining units — an average of 27 workers per store — are making only a modest impact on the impressive number of new union members in 2022, when Starbucks, and Amazon’s JFK8 facility in Staten Island, are combined, these two campaigns account for nearly a third of new union members this year (13,638 of 43,092).

The challenge will be maintaining organizing momentum, at Amazon, Starbucks and beyond, as the labour market softens — a goal to which the U.S. Federal Reserve, like the Bank of Canada, seems firmly committed.

The successes of the Amazon Labor Union (ALU) in New York, and Starbucks Workers United throughout the U.S., have led to discussion and debate in recent months over various aspects of union organizing and strategy. For some, the contrast between the ALU’s win in New York and union losses at Amazon facilities in Alabama and Alberta — campaigns led by the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union and the Teamsters, respectively — raises questions concerning what roles rank-and-file initiative and worker autonomy from established unions played in the ALU’s case.

However, we should be cautious to not overstate the role of “independent unions'' in the recent labour upsurge. While the ALU remains unaffiliated with any established union, Starbucks workers are backed by Workers United (an affiliate of the Service Employees International Union, SEIU), the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers represent new union members at Apple in Maryland, and the United Food and Commercial Workers are organizing at Trader Joe’s.

The ALU does, however, seem to be defying some standard organizing precepts. For example, the independent union filed for union election at the NLRB with the minimum number of registered members, 30 per cent. Seasoned union organizers recommend petitioning for an election with 60 to 70 per cent to hedge against the loss of support likely to follow the boss’ anti-union campaign. Amazon’s high turnover rate convinced the ALU that securing this latter level of support over time was unlikely and instead opted to build a core of committed members and combine this with maximum outreach to new workers ahead of the vote.

Although the ALU’s success using the above approach may lead some union leaders to question long-standing organizing tenets, a single case is hardly enough to throw the old rule book on the trash heap. The takeaway from the Staten Island example might simply be that in high-turnover workplaces, unions with membership levels closer to the NLRB threshold can still win elections, not that unions don’t need to build supermajority support in most cases.

It may not necessarily be that the ALU has invented a new formula, but rather that established unions haven’t been doing enough of what works. As Eric Dirnbach summarizes, research into organizing strategies over the past couple of decades shows that well-financed, strategic campaigns that utilize a variety of tactics to build worker power and counter the bosses’ anti-union fight can be quite successful. The key components, then and now, are adequate staff and resources, benchmarks, and assessments to gauge success throughout the campaign, and a rank-and-file committee to put workers in the lead inside the workplace. The ALU leaned heavily on this last tactic; other unions haven’t done so.

It’s notable as well that in Canada, campaigns at Starbucks and Amazon so far have been undertaken by established unions in a more direct fashion. The United Steelworkers are organizing at Starbucks in Alberta and British Columbia — building on the one unionized store they already had in Victoria, B.C. The Teamsters have ramped up organizing efforts at Amazon in Ontario and Alberta, while Confédération des syndicats nationaux (CSN) take the lead in Quebec. Granted, Canada hasn’t seen an organizing upsurge comparable to the one taking place in the U.S., but the fall in private sector union density also hasn’t been nearly as dramatic here.

This seems to me the biggest takeaway from the recent organizing push in the U.S. American unions and workers are so deep in the doldrums, operating in such a hostile legal environment, that some innovation — perhaps including more use of independent unions — has become inevitable. Critics may, justifiably, harp on American union leadership for its lack of vision and determination when it comes to new organizing, but to a certain extent union leaders have been making a rational decision not to expend substantive resources on bringing in new members when the prospects for success over the past decades have been so meagre.

Indeed, as Chris Bohner has recently demonstrated in Jacobin, American unions are hardly in financial crisis. Over the past 20 years, as U.S. union membership declined by 13 per cent, the value of unions’ net financial assets grew by 153 per cent. According to Bohner, “fortress labor” has chosen to prioritize growing its balance sheet through dues increases and its streams of real estate and other investment income, rather than employing more organizers and unionizing new workplaces.

Could the labour upsurge so far this year change the union calculus? Perhaps. But it’s far too soon to tell. Dan DiMaggio and Angela Bunay at Labor Notes see hope for optimism. They write: “The organizing wave is turning the labor movement’s prevailing wisdom on its head. Until now unions have mostly avoided filing for election at single workplaces that are part of big chains, like fast food restaurants or Amazon warehouses, not seeing a viable route to a first contract.”

On the other hand, these new high profile organizing campaigns haven’t entirely proven the “prevailing wisdom” wrong. None of the workers at newly organized Starbucks, Amazon, Trader Joe’s, Apple or Target locations have managed to begin collective bargaining with these corporate giants, let alone ratify a first contract. Unlike labour legislation in most Canadian jurisdictions, the National Labor Relations Act doesn’t provide for first contract arbitration. American employers have immense latitude to endlessly stonewall and exhaust new unions at the bargaining table.

New organizing in the U.S. is both promising and inspiring — and one hopes more of it spills over into Canada. But, unless this labour upsurge can also be harnessed to the task of reforming American labour law — a task which will require the resources and expertise of the established labour movement — workers will continue to face an uphill battle.

Member discussion