Canada has perhaps the narrowest “right to strike” of any capitalist democracy.

As I’ve covered before in this newsletter, the “right to strike” that does exist is frequently violated and circumscribed by federal and provincial governments through back-to-work legislation and other interference, directed at public sector workers and unions in particular.

Government repression — or the threat of it — is of course a major concern. But there’s also an additional way in which the right to strike is limited in Canada: it only applies to workers who are members of unions. If you work in a workplace with no union, you and your coworkers have no legal right to strike or engage in any collective action.

To get a sense of why this matters, it’s helpful to consider a counter example. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, workers at Amazon, Whole Foods and many others corporations in the United States, struck and engaged in other forms of workplace actions to protest their employers’ substandard pandemic preparedness and perceived lack of concern for worker health and safety. In some cases, these workers went on strike to demand additional hazard pay.

Had similarly situated, nonunion workers in Canada engaged in comparable actions, their employers could legally terminate them for breaching their employment contracts. Nonunion workers in Canada can individually refuse to work if they feel conditions are unsafe — a right that is notoriously difficult to exercise in practice — but they have no legal right to take collective action to protest their working conditions or put pressure on their employers.

The narrow scope of the right to strike in Canada has long been recognized as a serious weakness in Canadian labour law.

Compared to the U.S., it’s much easier to certify a union in Canada, though the task can still be daunting for workers in particular industries or workplaces. At the same time, the Charter-protected right to freedom of association only applies to recognized trade unions who have won a majority of support in a workplace. Workers seeking to form or certify a union must do so through the “proper” channels set out in provincial or federal labour relations acts, which involve submitting a specified percentage of signed union cards and then winning a labour board-supervised election (unless you’re in a province which allows “single step” or card-check certification, like British Columbia). In other words, workers can’t go out on strike to compel their employer to recognize and bargain with their union.

Canadian union members are much better protected than their American counterparts when they do exercise their legal right to strike — though that’s not saying much. Canadian strikers are entitled to return to their job after a strike, whereas American union members who go on strike can be “permanently replaced.” In Quebec and B.C. — and perhaps soon in the federal jurisdiction — anti-scab laws prohibit employers from even temporarily replacing strikers for the duration of the work stoppage. Thus, to varying degrees, unionized workers enjoy much stronger protections in Canada than they do in the U.S.

Yet even when Canadian workers have a certified union in their workplace, the right to strike is extremely narrow. Most notably, workers can’t strike during the life of a collective agreement. This is known as the prohibition on “midterm strikes.” Instead, if an employer is violating the terms of the collective agreement, the union must file grievances, and disputes are typically sent to a labour arbitrator. A union that engages in a work stoppage when a collective agreement is still in force could face financial penalties, even if the “strike” causes no economic harm to the employer (for example, if the work stoppage is short and lost production is made up after the return to work). These are referred to as “punitive damages” and are meant to act as a deterrent against “illegal” strike activity.

Furthermore, a union must exhaust collective bargaining and government conciliation and conduct a successful strike vote demonstrating that a majority of workers support striking before they can hit the picket line. Failing to achieve a successful strike vote is a clear demonstration to the employer that the union is in a weak position. It also means that it’s irrational for unionized workers to ever vote “no” during a strike vote, even if they don’t intend to strike. A strong strike vote sends the bargaining team back to the table with a credible threat and additional power. But most importantly, no strike can be declared until the vote is held.

As onerous as all these restrictions are, perhaps the most glaring is the prohibition on strikes of nonunion workers. In Canada, our labour legislation protects “trade union association,” not freedom of association more broadly. Consequently, if or when a group of workers come together to confront their employer — whether they intend to strike or just convince the employer to sit down and meet with them — labour law doesn’t protect them in any way unless they first certify a union.

On the other hand, American workers have broader protections for collective action — at least on paper. The key difference is that section 7 of the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) protects what are referred to as “concerted activities,” whereas labour relations laws across Canada protect a narrower range of “trade union activities.”

Concerted activities include any collective action, including work stoppages, “for the purpose of collective bargaining or other mutual aid or protection.” Importantly, workers don’t need to be current members of a certified trade union to be covered by this section of the NLRA. In other words, workers who engage in a strike to protest conditions at their workplace are protected from employer retaliation by section 7, whether or not they are unionized. Although U.S. employers have considerable leeway to “permanently replace” striking workers, whether unionized or not, the National Labor Relations Board can reinstate workers who are fired for engaging in “concerted activities” and fine employers who retaliate against such workers (both of which they do, from time to time).

Canadian nonunion workers have no such right to strike or protection from employer retaliation.

When union density was higher in the private sector, Canada’s more restrictive right to strike might have made a certain amount of sense (though this too is debatable). Access to unionization and the various protections it confers — bargaining in good faith, interest arbitration, etc. — meant that workers were less likely to need broad protections for disruptive activities outside of official union channels. However, that long ago ceased to be the case, if it ever was. Private sector union density has declined considerably over the past several decades and many workers find themselves with only limited employment standards and occupational health and safety protections at work. These nonunion workers effectively have no statutory protection if they collectively stand up to their bosses.

Nonunion workers who experience employment standards violations, such as wage theft and other forms of payment issues, find that filing complaints through the official legal channels is an extremely time-consuming and onerous task. Research demonstrates that the majority of employment law violations are not detected or punished, primarily because workers don’t report the infractions. A common reason for this is that workers, quite rationally, don’t believe the employment standards complaints process will ultimately resolve their issues.

American workers who are not members of unions and who experience wage and hour violations at least have the option of organizing to have these issues redressed. Indeed, there are many examples of workers organizing, staging walkouts, calling strikes of short duration, and engaging outside community support to fight back against violations at work.

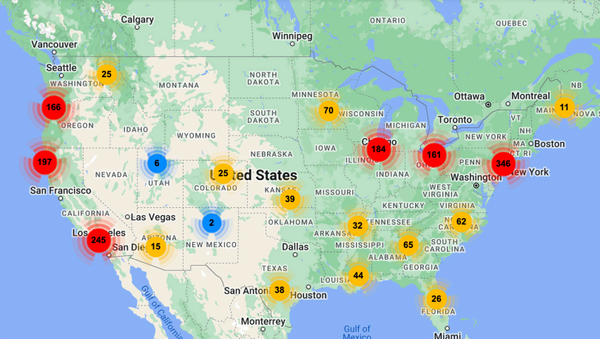

About a decade ago, Walmart workers in the U.S. engaged in a series of strikes involving 28 stores across 12 states. Backed by Organization United for Respect Walmart (which was financially supported by the United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) union), these nonunion workers stopped work to various extents to protest low pay and bad working conditions at Walmart — a notoriously anti-union employer.

Again, section 7 of the NLRA protected these workers from discipline for their “concerted activity.” Were Walmart workers in Canada to engage in identical action, they would’ve been breaking the law and could’ve been subjected to employer discipline, including being fired. Even if a union or union organizer was helping these workers in some way, financial or otherwise — as was the case with UFCW at Walmart — this wouldn’t make any difference. Nonunion workers would still be breaking the law by striking — and the union could in fact be liable for damages to the employer for inducing breaches of employment contracts.

Of course, none of this is meant to suggest that nonunion Canadian workers can’t “unlawfully” strike to force change at work and beyond. Canadian history is full of examples of workers doing this, including in order to win the system of industrial relations and labour law we presently have. The point is that when they do so, they have no legal safeguards.

At minimum, all workers — whether they are members of a union or not — should have the legal protection to strike and engage in other work stoppages and collective action, free from employer retaliation. Ideally, labour legislation should be enhanced so that nonunion workers also have a right to make collective demands on their employers, even if they haven’t certified an established trade union yet. This reform could also include a requirement that employers must meaningfully engage with any group of workers who make a collective demand. Labour law scholar David Doorey refers to this as “graduated freedom of association” and has been advocating for such a model for many years.

In some cases, these “thinner” freedom of association rights could lead to workers taking initial collective action that leads to union certification. In other instances, it might simply provide legal protection for “one-off” actions or for alternative models of labour representation (for example, by worker centres or other public advocacy organizations). In any event, “graduated freedom of association” would extend legal protection and allow greater numbers of workers to take risks and fight their bosses.

It’s time to expand freedom of association and the right to strike to nonunion workers. While protecting these activities for nonunion workers is no panacea for declining union power, it would create a set of protections for workers in vulnerable positions to collectively organize and engage in the sorts of direct action that frequently deliver the goods for the working class.

Member discussion