A white supremacist paramilitary group called “The Base” made international headlines in recent weeks as authorities in the United States arrested some of its alleged members over the course of a few days ahead of a pro-gun rally in Virginia.

One of the six people arrested was Patrik Mathews, a 27-year-old former Canadian army reservist who’d been “missing” since August 2019. Mathews became a combat engineer in the Canadian military and worked his way up to becoming a master corporal with Winnipeg’s 38 Canadian Brigade Group. In other words: he’s an expert at making bombs.

Mathews left his Manitoba home soon after a report by Ryan Thorpe at the Winnipeg Free Press came out that exposed his alleged involvement with The Base. Mathew’s red 2010 Dodge Ram truck was then found near the U.S.-Canada border, and authorities suspected that he’d illegally escaped into the country. It was later reported that Mathews was being harboured by members of The Base in Delaware, where he was eventually arrested.

Among other things, Mathews is accused of recruiting for The Base while still with the military and stationed in Manitoba. He’s since been voluntarily released from the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF).

Those arrested have been charged with conspiracy to commit murder, including of antifascist activists. Mathews himself allegedly talked with his buddies about killing a cop and others at the gun rally. Later on, the FBI found out other Base members thought Mathews was so incompetent and such a liability that they’d even talked about murdering him. Mathews now faces 60 years in prison.

It’s a wild story filled with twists and turns, enough to make anyone wonder how a guy like Mathews, who isn’t shy about expressing his views — there are videos of him talking about violent, racist revolution while wearing a gas mask — managed to become and stay an army reservist.

The question is a useful entry point for anyone willing to examine the connection between the Canadian military and violent white nationalism. Existing links have become clearer over recent years thanks to good reporting and public pressure. But whether the CAF has the ability to protect itself structurally from those who harbour hateful ideologies and intentions remains unclear at best.

For people such as Base members, who fantasize about a race war, the military is a place to keep your head down while acquiring serious training with deadly weapons. It’s also an institution they see as fighting the bad Islamist terrorists abroad, a cause long championed by those on the far-right in defence of Western Values.

As the public increasingly witnesses individual service members getting exposed for active participation in white nationalism and extremism, more has also been revealed about how the Canadian military operates its own opaque system of handling these cases.

These details of how and why certain decisions are handed down to those accused of participating in hateful activities remain sealed to the public. But what’s been disclosed thus far offers a clear enough image of the disconnect between the CAF’s handling of the issue and the obvious implications such decisions have on the wider society.

The military confirmed late last year that they’re investigating yet another reservist, Tony McKay, who posted at least a handful of times in 2016 on a now defunct white nationalist forum, Iron March. McKay used the forum to argue Adolf Hitler “wasn’t the devil” and doesn’t deserve such a bad rap in contemporary society. He’s currently being investigated by the CAF.

The Atomwaffen Division, another violent neo-Nazi terrorist network, used Iron March to announce its existence in 2015. Two pioneers of the group — Devon Arthurs and the group’s founder, Brandon Russell — both spent time on the forum, and McKay admitted to knowing them.

Then there’s Canadian Royal Navy reservist Boris Mihajlovic, an Iron March administrator and one of its most prolific posters, who encouraged his fellow white nationalists to enlist in the military while also allegedly arranging an arms sale through the forum.

These Iron March-related revelations came to light after an anti-fascist hacker released a huge trove of personal data, including IP addresses and emails, of those who registered on the forum. The data indicated that around 88 users were located within Canada.

It’s now confirmed the CAF knew they had white nationalists within their ranks as early as November 2018, when the Military Police Intelligence Section published an internal report regarding rising concerns of right-wing extremism in the military.

First obtained by Fabrice de Pierrebourg of Montreal radio station 98.5 FM, and shared publicly in May 2019, the report shows that 16 members within the armed forces were linked to six far-right groups: Atomwaffen Division, La Meute, III%, Hammerskins Nation, the Soldiers of Odin and the Proud Boys. The document noted that, “All of the groups identified fall under the far-right spectrum of political discourse and beliefs, specifically anti-Islam and/or white supremacy.”

The document also stated that between 2013 and 2018, 51 CAF members “were identified as either being part of a hate group, or … undertook actions and/or made statements which could be viewed as discriminatory or racist.”

Sixteen of the 51 had serious links to the six aforementioned groups, while the other 35 were reported as having either made statements or taken actions that were motivated by hate. As of November 2018, when the report was published, nine of the 16 — six regular force members and three reservists — were still in the CAF.

Fifty-one people doesn’t amount to a large percentage of the Canadian military, but a single person today, armed with the right tools or weapons, can still end up doing a lot of damage. A paramilitary of trained white supremacists has the potential to wreak unspeakable havoc and death. Moreover, the fact that an internal report was done suggests the CAF didn’t want the public to make a fuss.

It was only after the report got leaked to the media that Defence Minister Harjit Sajjan — a Sikh who has spoken about facing “a lot of racism” while in the CAF — announced he’ll be asking the force’s ombudsman to do an in-depth internal probe into racism in the military.

Additionally, the office of Canada’s Chief of the Defence Staff Jonathan Vance, the number two ranked member of the CAF, is also conducting a concurrent investigation into best practices on how to handle hate and extremism.

Much of this was unlikely to have taken place without endless prodding by the media and civil society groups such as the Canadian Anti-Hate Network. It clearly took public pressure and fear of embarrassment for the government and military to launch further inquiries into the issue.

A CBC report released last December, based on an internal memo written for Sajjan, also showed the military actually doesn’t have any specific service offences to punish those who display hateful conduct. Harsh penalties can result from judgements handed down by the military court or through the Criminal Code, but existing data shows just how rare such instances are in reality.

The CBC report specified, with help from a former military legal officer, that, of the 51 aforementioned cases, only four resulted in real discipline. The CAF has also confirmed that 15 were either let off with a warning or assigned remedial measures such as counselling or probation. Eighteen were medically or voluntarily released and, as of last December, another eight are still being investigated. Three were kicked out for good, which is as bad as it gets.

The key takeaway is that the military isn’t itself a public court of law. Its administrative measures are kept secret, which means the majority of cases are handled behind closed doors.

Furthermore, the practice of simply discharging someone who’s been accused of either expressing hate or associating with hateful groups may help cleanse the military, but it’s not particularly useful to the wider public. Discharging someone “voluntarily” can simply mean the CAF wants to take the easy route and avoid a trial via the military courts. It also means that the CAF is releasing a possible white supremacist or extremist into the civilian population, usually armed with formal military training in weapons. They live like normal people and those around them wouldn’t know anything about their issues in the CAF.

There’s simply no real consideration by the CAF for the wider implications of letting problematic soldiers go and not telling anyone, including law enforcement. Clearly, as demonstrated by cases and individuals like Mathews, the implications of how the CAF acts has potential life and death consequences. The disconnect can be deadly, and some of the more extreme consequences can already be seen in the U.S.

Investigative reports, such as one published by ProPublica in May 2018, show that white nationalist paramilitaries such as Atomwaffen have been successful in recruiting out of the U.S. Armed Forces. This includes a marine who participated in the violent Charlottesville white nationalist rally in 2017, where an anti-fascist protester was killed.

The Military Times, an independent outlet covering the U.S. Armed Forces, conducted a survey in 2018 and found that 22 per cent of service members “have seen signs of white nationalism or racist ideology” among their ranks.

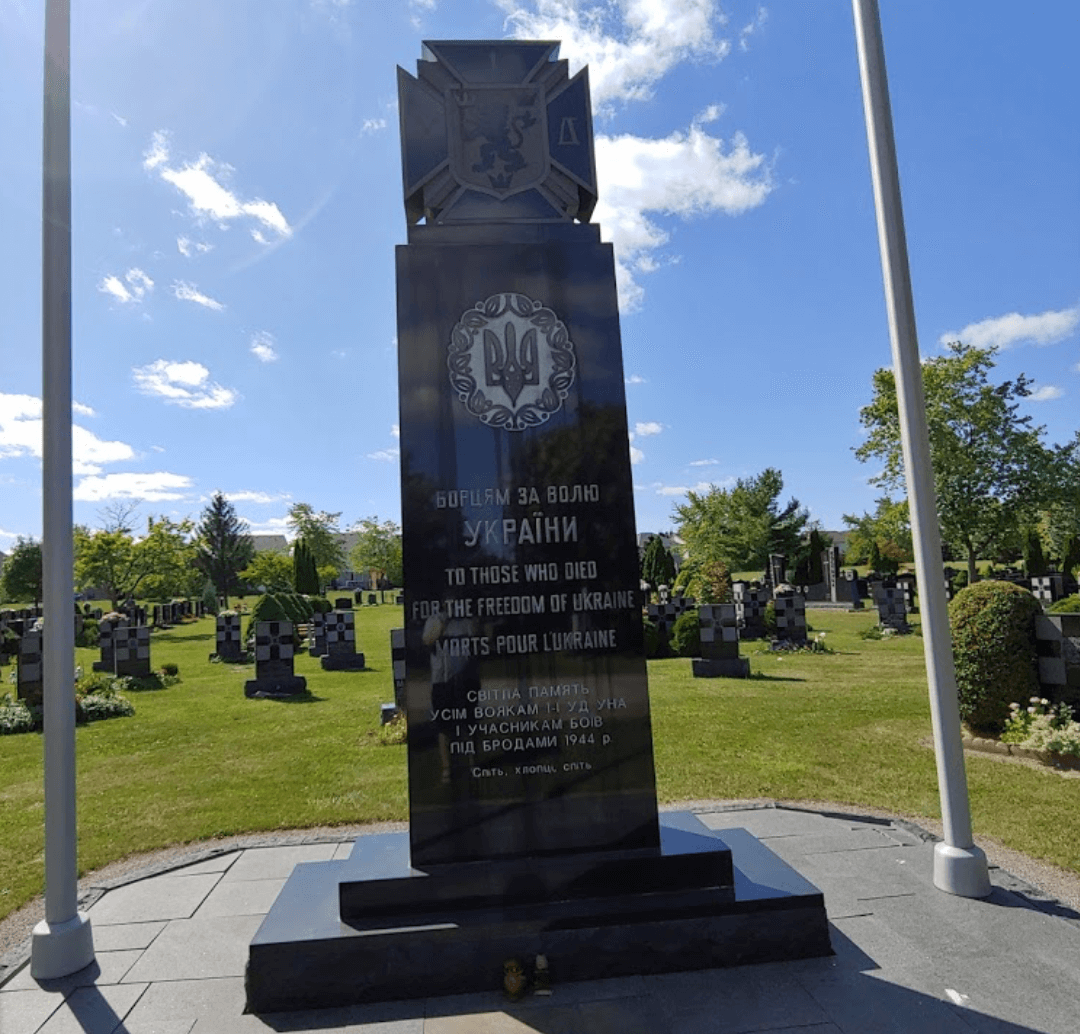

Plenty of white nationalists dream about sparking a race war or at least throwing themselves into situations around the world where a conflict involves those who think like them. One example is how Atomwaffen connected with Ukraine’s far-right Azov Battalion, which plays a role in the country’s conflict with Russia. The military offers an option where violent far-right extremists dreaming of a racist apocalypse can get free training.

Then there’s the fact that a cornerstone of far-right organizing revolves around Islamophobia, including visions of an ultimate showdown between the Western world and the “Islamist hordes.” The military, whether it likes it or not, is seen as a possible avenue through which white nationalists can exercise that vision in places such as Afghanistan, where the Canadian military has long fought the Taliban.

These admittedly complex issues aren’t something the CAF seems to be able to address at a systemic level. They need to, because those who end up suffering the consequences live outside the world of the military and don’t have the training to shoot back.

Member discussion